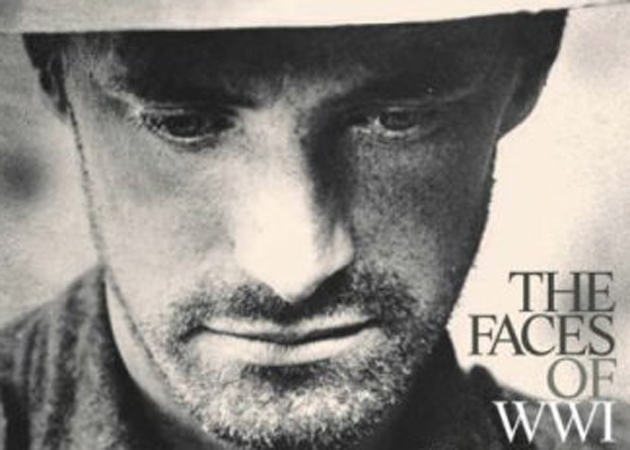

A serial story about WW1 loosely based on true events. The series was published this week in the Pembroke Daily Observer (with different pictures and layout) and was written by Owen Hebbert (My seventeen year old brother in case anyone is wondering.)

"the best piece of fiction writing that this old editor had ever seen" Peter Lapinskie, Managing Editor for The Daily Observer

**********************

Rain fell across the battlefield in a heavy, imposing manner. It came in thick, blinding waves like the wash of a sea. There was no lightning and subsequently no thunder, but the sky was so replete with clouds that were one uninformed one might have thought it night rather than day.

In the trench it was hell. Water ran in cascades down the mud walls and gushed in black, frothing rivers over the trench floor. The men were halfway up to their knees in it. There was almost nowhere that they could go to get away from the rain. Those sitting on benches that lined the walls of the trench had to be resigned to getting not only their shins but also their laps wet as rain continued to pour in and water fell down from directly over them in long, streaming drips. Worse than this was the rats. Hundreds of rodents, fat from months of feeding on human refuse and bodies, were drowning – and not quietly.

“Bloody cold,” James Lawrence said. The young English corporal shuddered and flapped his arms across his chest, sending a spray of muddy water into the face of the private beside him. “Sorry about that, Cramer.” Lawrence apologized, rolling his shoulders miserably.

“Forget it,” Cramer said, wiping his bare hand across his face, a wholly vain effort in hygiene as his hand was muddy and dripping rainwater. Jonathan Cramer was young. Not young like Lawrence was young but much younger still. The boy’s face was acne-ridden and the baby fat that still clung to his cheekbones contrasted strongly with the firm set of his jaw and the deep bags under his eyes. The youth was withdrawn and had always avoided conversation with his fellow-soldiers. Deep within his sunken eyes, and under his youthful face was a secret that his nervous, fretful disposition caused to prey on his mind.

“How old are you Cramer?” Lawrence asked, sucking the rainwater off his lips and spitting it back out into the water swilling around his legs.

“Sixteen,” Cramer said in a low voice. Like hell he was sixteen.

“Really?” Lawrence smiled at the kid. Cramer wasn’t looking at him, but was busily occupied with chewing the corner of his mouth off instead. The boy was obviously younger than that. Fifteen or an older fourteen. The carbine clutched in the youngster’s hands seemed humorously unthreatening. What does a boy like that do when he breaches the trench? They call it cannon fodder.

“Why’s the water doing that?” Cramer asked, sullenly changing the subject.

“Doing what?” Lawrence followed the boy’s gaze and found himself looking at the black flood his feet were immersed in. He really wasn’t all that interested in talking about water in any form right then. He took his peaked cap off and tapped it on his forehead to knock the rain off before pulling it back over his lank black hair.

“It’s sort of swirling there,” Cramer said, pointing.

Something in his voice, an oddly uncharacteristic strain of insistence, made Lawrence look again. The trench was as dark as late dusk and the water was darker than hell, but in the light from the sputtering kerosene lantern carried by a passing sergeant, the surface of the water was somewhat illuminated.

And Lawrence saw it. A single, thin whirlpool with a diameter of about two inches was spinning furiously.

“I’ll be a son-of-a-gun,” Lawrence breathed, leaning closer.

“Where’s it going?” Cramer asked, also leaning forward, impressed that the small nothing that he had chosen to change the subject was so genuinely interesting.

“I don’t know but it’s going steady. Somewhere there’s a big space that’s taking a lot of filling,” Lawrence said thoughtfully.

“But what? There’s no space under this is there? I mean, I wasn’t here for the digging but I don’t think we have anything here. Unless there’s some kind of a storage cell under the boards of the trench floor. Do think that there are supplies getting wet?”

“Storage cells be hanged!” Lawrence snapped. He straightened and rose. “Sergeant Durst!”

The sergeant turned and looked over towards the speaker, raising his lantern to see better which of the soggy, mud-coated men was speaking. He saw Lawrence standing and nodded curtly, not interested in being detained when he could go stand in Major Heath’s small dugout while delivering his report. “You have something of importance to report, Corporal Lawrence?”

“It’s just a small matter, Sir.” Lawrence pointed down at the mysterious indication of a drain.

“What is it man?” Durst demanded, squinting past his lantern at the patch of dark, swirling liquid being indicated.

Lawrence leaned closer down, stabbed his gloved finger at the whirlpool. He didn’t speak, forcing Durst to come closer to inspect.

“Well?” Durst seemed unimpressed. “It’s water. You have some in your ear. If it weren’t there you might have heard that I asked you if you had anything of importance to report.”

“The water’s draining, Sir,” Lawrence said.

“Then it has my blessing. Is that all, Corporal?”

“Sir,” Lawrence said carefully, “the water shouldn’t have anywhere to be draining to.”

“Then it isn’t draining, man! Do you need me to take this apart for you? Idiot!”

“Sir…”

“Shut up!” Richard Durst couldn’t believe that he was having this argument when the major was awaiting the routine report. “Shut up!”

“Yes, Sir,” Lawrence saluted and sat back down on the bench. The warmth from when he had been sitting there before was already washed away by the torrent that crashed loudly down on them from the merciless skies.

Richard Durst turned and started wading away through the trench. The man had been making fun of him. Water draining. The subordinates could be such stupid blighters. Durst was devoted to serving his king, his country and his major. Unadulterated passion for noble causes drove the man and got him recognized and promoted. Men like Lawrence were spiteful over the apparent ease with which such sincerity bought the go-getters favour. Mind, Corporal Lawrence wasn’t a common perpetrator of disrespect. What had the man been thinking? Water draining, indeed. In the trench! What was supposed to be obvious there?

Then it clicked.

“Bloody hell!” The sergeant turned and stared, his expression one of dawning horror, at Lawrence. The corporal nodded, his face softening as he saw that Durst was catching on.

“You!” Durst shot his hand out and pointed to Cramer even as what felt like a full inch of rain fell from the sky and slammed over them, drowning his words out in a whirling scream of wind and water.

“Me?” Cramer pointed to himself, guessing at the intent of Durst’s gesture.

“Tell Major Heath that something of considerable importance has turned up! Go! Run, boy!”

Water crashing up on either side in wings of black, frigid water, the private plowed off through the flooded trench. Durst and Lawrence studied the whirlpool in the light of the lantern. The unspoken fear that they both felt was understood and not stated. There was only one reason that there would be a large space under their trench.

The Germans had tunneled across no man’s land.

It was about then that the lightning storm started.

“When did you find this, Corporal?” Sergeant Richard Durst asked tersely.

“Just as you were going by, Sir. Private Cramer saw it.” Corporal James Lawrence shivered as rainwater ran down the small of his back.

“Observant. Run and get me two shovels.”

“Yes Sir!” Lawrence turned and ran.

“Bloody observant,” Durst muttered, straightening. He carefully took the glove off his right hand, put it in his pocket and rolled up his right sleeve. Overhead the thunder rumbled and then cracked like a whip. Bending over, Durst submerged his hand in the muddy water and felt about the slimy trench floor. At first, the senses of his hand were so numbed by the cold, the wet and the slimy soil that it didn’t register anything but discomfort. Then he felt it. The harshest point of the current directly over the drain. Water gushed through his fingers and disappeared between a pair of smooth, ice-cold rocks.

“Shovels, Sir!” Corporal Lawrence was back, holding two short trenching shovels.

“Sergeant!” The voice was cold with an edge like serrated knife-blade.

It was Major David Heath. Private Jonathon Cramer, who had been dispatched to call for the major was close behind.

“Sir!” Durst turned, straightened and saluted. He was older than Heath, which wasn’t saying much. As so many officers had been killed during the war, young men like Heath were being quickly promoted to dangerous positions of authority.

“You saw fit to have me called for?”

“Sir, yes, Sir.”

“Well speak man! What is it?”

Durst was not a man to quibble. He was frank and came straight to the point. “I think that the Germans have tunneled under our trench.”

Heath was silent for the space of about five seconds. He glanced at the three men standing in a semi-circle in front of him. They were all part of his regiment and he knew them all. He had met Sergeant Durst and Corporal Lawrence on previous occasions and Private Cramer had introduced himself just minutes earlier. The words that had just escaped Durst’s lips were not, however, heard by this limited assembly alone. Whispers and despairing moans erupted from the dozens of men all about them and in an instant word was passed throughout the trench.

“Why?” Heath asked.

“Water is draining at this point,” Durst indicated the whirlpool and lowered his lantern so that the major could see more clearly, “and it isn’t stopping.

“The bloody Germans have tunneled under us!” A frantic voice gasped.

“That’s it!” A mid-aged private rose and began clambering at the trench wall that led away from no-man’s land.

Heath whipped out his revolver and aimed it at the deserter’s head. “Don’t make a move, man, or I shoot your stupid brains out! We don’t know that there’s a tunnel! Dying while running from something that isn’t there would be one hell of a daft way to go!”

For a moment the only noise was the thunder, the rain and the plaintive shrieks of drowning rats. The Webley Mark VI was no gun to fool with. It’s .455 bullet could knock off almost any part of the body and utterly shatter the thickest of bones. Should Heath missed the man’s head and hit a non-vital area, the death would only be slower as a shattered arm or leg in the trenches meant guaranteed gangrene.

Slowly, carefully, the would-be deserter slid back down into the trench.

Heath’s attention quickly moved back to the matter of the drain. “Lawrence and Cramer? I want you to ascertain the truth. Dig this drain out. It’s probably nothing, but we mustn’t be caught with our trousers down.” Heath stepped back and allowed the two men to start digging. As he holstered his revolver, he turned to Richard Durst. “Sergeant, you may deliver your routine report to me now.”

Lawrence had been soaked and muddy before he started digging but now he was feeling like a perfect porpoise. Digging mud under a foot of water while heavy rain poured down from above was disgusting, back-breaking work, especially using the short little trenching shovels. However, it was not wholly unsatisfactory. As more and more watery filth was shoveled aside, the intensity of the drain picked up.

“There’s definitely something there,” Heath said thoughtfully, interrupting Durst’s report. “Your shovel, Mr. Cramer?” Heath took the shovel and prodded at a rock exposed by the rushing water. There was a sucking noise and the small boulder disappeared, leaving a gaping hole in what should have been a solid trench floor. The water soon filled the gap, creating a powerful current around the men’s ankles.

“A tunnel,” a nearby soldier breathed.

“I’m just about through,” the private that had tried fleeing said coldly. “I’d rather take a bullet in the head from a Brit than from a Hun. Hell knows when they’ll start pouring up into here with their grenades and knives and guns. We’ll all be crucified. I…”

David Heath turned around so fast that his greatcoat swirled like a cape. “You will die, man, if you say another word.” The young officer’s gun was back out and was aimed, as steady as a pin in a vice, at the private’s face. There was a moment of silence and then the gun was lowered and holstered. Sweat stung Heath’s face.

There were about forty men standing where Major Heath could see them. Faces were somber and unhappy; hands gripped Lee-Enfields as though preparing to shoot down whatever might erupt from the gaping hole in the ground through which water still fell.

“I need a volunteer to lower himself through this hole,” Heath said.

The ranks of gathered men visibly shuddered and many drew back to avoid being mistaken for volunteers.

“Sir?” A quiet, immature voice called.

Lawrence stabbed his shovel into the ground and turned away. He wrapped his arms around his chest and shivered, unable to stand what he knew was coming.

“Yes Mr. Cramer?” Heath said, turning to the boy.

“I’ll do it, Sir.”

“You’re small enough,” Heath said approvingly.

“Permission requested to accompany Private Cramer,” Lawrence asked, his voice harsh.

“Permission granted,” Heath said approvingly.

The two men dropped into the tunnel and a lantern was lowered to them.

For about five minutes there was total silence save the rumble of thunder.

“Major! There’s something down here you should see!”

Heath raised his eyebrows and climbed down into the tunnel as well. For a moment he couldn’t see anything save the harsh glare of the lantern that Cramer was holding. Then he saw it. Piled high at the end of the tunnel was a mound about three feet high of wired dynamite.

Heath reached over and extinguished the lantern that Cramer was holding. “Bleeding hell,” he whispered.

*************************

Back in the trench the suspense was incredible. Neither Lawrence or Cramer dared tell what they had seen in the darkness of the tunnel below their feet and Major David Heath seemed disinclined to divulge the information himself. The major sat on a bench, smoking a cigarette with a feverish intensity. It was still raining and the lightning storm was directly over the battlefield, deafening and blinding the men as it struck down on the metal-littered no-man’s land.

After about ten minutes of dangerous quiet, Heath rose and straightened. He looked at the thirty or so men that were sitting on benches where he could see them (the zigzagged nature of the trench only allowed him to see so far). “Men,” Heath said, “pay attention!” Lightning flashed and water slammed into the young officer as he began talking. “Circumstances have arisen that call for a dangerous mission to be executed. Even as we speak, the enemy has a sizeable stash of wired dynamite stowed under our trench. That is what their tunnel was for. I have decided that we must physically carry it back under no man’s land. My reasons for arriving at this conclusion are for the good of this war. Now there will need to be four men so that the dynamite will be transported with as much safety as can be afforded.”

“Right!” The middle-aged private who had attempted to desert earlier stood and waved a scornful hand in the major’s direction. “Which four of us want to go into that bloody hell-hole and carry dynamite around in the dark? And you know another thing? The Germans have those bombs wired and there’s no way to know when they’ll decide to shove a plunger down and scatter your insides from here to freakin’ Brandenburg!”

“What you say is true,” Heath said evenly, “and whoever volunteers should know that.”

The private sat back down as did anybody else that had been standing. Volunteers appeared to be scarce.

“However,” Heath continued, “I think that whoever volunteers should also know that I’ll be down there with them. I only need three volunteers. I will be leading them.” The young officer stood straight as a ramrod, his youthful, unshaven face dripping rainwater and his gloved hands clasped behind his back.

This was different. Here was a leader who, in the most miserable, dark, freakishly-horrible conditions was still willing to stand by principles of loyalty and self-sacrifice.

“What…” The private pointed an uncertain forefinger at Heath. “You’re going to go down there and carry the dynamite?”

“We mustn’t waste time with talk,” Heath said stiffly. “Have I any volunteers?”

“I!” Sergeant Richard Durst stepped forward.

“I!” Private Jonathon Cramer offered his services.

“Then I, too!” Corporal James Lawrence came to stand beside the boy.

“That’s three volunteers. We’ll need four trench-clubs. Would somebody…”

The rebellious private was already on his feet and running for the nearest weapons dugout.

Armed with their clubs which swung from their wrists by leather thongs and with the assistance of two electric lights, the four men dropped into the tunnel, leaving the cold, wet, loud, dying world above them and entering a hell beneath hell. They loaded all the dynamite stacked there into delicate armloads of death.

“All right!” Heath said, “now we must advance down the tunnel at the same pace, or else the cord will pull and the dynamite might go off. Sergeant Durst and Corporal Lawrence, you two are in charge of the lights. Hold them in your mouths and whatever you do, don’t drop them on your load of firecrackers or there’ll be a big crater in the middle of no-man’s land. Now ever so carefully, forward!”

The journey through the tunnel was one that is hard to describe. After the men had walked for about ten yards the floor under their feet became flooded and they were gingerly creeping over slippery boulders hidden under water that was sometimes two feet deep. The electric lights were little good, especially after Durst dropped his in the water. For twenty yards the floor remained flooded and then it rose sharply. The men emerged from the water to step into a bank of ankle-deep mud.

“This is suicide,” Cramer murmured under his breath. The boy’s every step was an act of great labour. His boots stuck in the mud and had to be dragged out with great effort. He was afraid of fooling about lest he drop his dynamite, and if he slowed up too much, the wires on the dynamite might jerk. After about five yards of negotiating the mud, he lost one of his boots and, finding that this made it easier, he quickly allowed the other to slip off as well. He would pick them back up on the return trip – provided that there was one.

“Sir…” Durst, who had been especially silent since he had lost his light, spoke for the first time. He struggled with his boot for a moment and then continued. “…Do you intend to leave this mess under the Germans’ trench?”

“Can you think of a better place to leave it?” Heath asked with a small smile that was lost in the dark.

“No, Sir,” Durst said quickly. He believed in his officer no matter what the young hothead might be doing. It was obvious that besides being gallant and selfless, this Heath fellow had a strong sense of practical irony.

They continued on in silence. For about fifty yards, the tunnel floor was actually dry. It was rough and covered in clods and stones, but dry nonetheless. It was on this ground that Cramer quickly regretted abandoning his boots. The boy’s feet were soon bruised and bleeding. The torture was increased significantly when the floor banked sharply and the four men were walking through water once more. The muddy swill stung at Cramer’s cut feet almost as bad as his own sweat had, but it was the sharp, gravel-like deposits in the water that made his every step agony.

Then they had to walk through more mud for about ten yards.

Suddenly Major Heath, who had conducted the entire journey without a single complaint, let out a quiet laugh. “Don’t speak too loudly, men, but I think that our little jaunt is at an end.”

Sure enough, in the dimming light cast by the electric torch, the end of the tunnel could be seen. The Germans had apparently boarded over the hole that they had used to dig the tunnel, as no light came down from above save a few rays that wormed between the planks of the cover. German voices and the sounds of thunder, rain, rats and the like could be heard. Water poured down through the slats of the boards and all four men quickly realized how relieving it had been not to have rain streaming down on them from above.

“Gently now!” Heath whispered. Slowly, tenderly, he placed his load of explosives down, careful not to put it under the drip. The other three followed suit. Heath made sure that the dynamite was still wired properly and, having given the mound a loving pat, drew back.

He smiled thoughtfully and said: “Mission accomplished.”

They all stepped back from the stack of wired dynamite, staring at it in horrified fascination. The Germans had tunneled across no man’s land and deposited this mother lode of explosives under the British trench, but it had been discovered. Major David Heath, Sergeant Richard Durst, Corporal James Lawrence and Private Jonathon Cramer had just finished carrying the deadly sticks back through the tunnel and placing them under the Germans’ trench.

“Shall we, gentlemen?” Major Heath waved an inviting hand towards the tunnel that led back to safety.

No second bidding was required. There was no telling when a German engineer might decide to depress the plunger of his remote detonator. The four men started running.

Private Cramer had abandoned his boots on their first trip through the tunnel and his bare feet, cut and stinging slowed him as he tried to keep up with the older soldiers. He was now carrying the dying electric lamp and its beam wavered dramatically as he stumbled and pitched through the tunnel.

Major Heath’s face was expressionless. His feet pounded steadily into the dirt, the mud, the water; his teeth sank into his cheeks as he tried to calm the flow of emotion that he felt. He felt fear, satisfaction, excitement, stress, but most of all, he felt his responsibility. The lives of these men and the leadership of his regiment back in the trench were his responsibilities.

They were about half-way across no man’s land when the dynamite went off. To the four men in the tunnel it sounded as though a large building had been picked up and dropped on another large building. Worst of all, it felt as though they were in the latter large building when it happened. For a brief instant a flash of painful light lit up the mud the men were standing in and then disappeared as the tunnel started caving in.

“Hang,” Cramer said softly.

“Run!” Heath’s order was scarcely audible as all the men’s ears had popped, but then it wasn’t entirely necessary anyway.

They ran. The electric light was gone – dropped, dead, forgotten. Slapping at the muddy tunnel walls with their hands, they felt their way through the darkness. Clods of earth and stones rained down on them from the tunnel ceiling.

“Who’s there?” Heath shouted as he ran. “Can anyone hear me?”

The rumbling of the tunnel collapsing was loud but above it came the affirmative shouts of Heath’s men.

“I’m right behind you, Sir!” That was loyal Durst.

“Here, Sir!” That was Lawrence.

“I’m coming!” This last voice, shouted out in a desperate, agonized tone of determination was that of Cramer.

“Keep yelling!” Heath shouted. “We mustn’t lose one-another!”

And so the men ran, shouting to each other and trying not to fall as they crossed the mud, the water and the short stretch of hard, dry, gravely ground that separated the long stretches of water. It was when they were about three-quarters of the way through the tunnel that the ceiling started raining down on them in earnest. Entire slabs the length of dining tables fell down amid showers of boulders and mud. Dirt filled the men’s eyes, ears, mouths, clothing and boots.

“Don’t stop yelling!” Heath roared above the colossal crashing of raining earth. “Yell your names!”

“Lawrence!” Corporal Lawrence cried.

“Durst!”

“Heath!” That was the major. Though they could barely hear him, his men thought his voice to have lost none of its authority and assurance.

“Cramer!” The boy private shouted.

“Lawrence!”

“Durst!”

“Heath!”

“I can see light!” Cramer shouted.

It was true. The end of the tunnel, heralded by rays of sunlight that streamed into the tunnel from the British trench above, was less than fifteen yards ahead of them. The sight gave the men courage and new energy. Shouting and laughing, ducking their heads to avoid the falling ceiling over them they raced forward.

Suddenly Heath heard a shriek and with safety no more than ten feet away, he froze. Every nerve in his body was stiff as a rod of iron. His ears were tingling as he tried to listen for the sound to repeat itself. He turned around, looking down the way he had come. It was hell in there. Behind him he could hear Durst and Lawrence being pulled up into the trench. Into safety.

Then he heard it again. His lips moved, disbelievingly mouthing a single name. Then he screamed it, tearing the breath from his aching lungs like a knife from a wound. “Cramer!”

He ran back into the darkness. Into the hell under hell. He couldn’t see a bloody thing. He ran to where he thought he had last heard Cramer’s voice. There was nothing there.

“Cramer!” He shouted. Suddenly his foot slipped, sending him into a deep puddle. He felt a stone scraping the skin off his knee as he landed. A clod of earth fell over his shoulder and knocked him down on his face. Pebbles and earth sprinkled across his back. He was going to be buried alive if he didn’t move. Fear gripped his heart and he struggled into a sitting position. From there he rose and threw himself against the wall where he was out of the way of most of the falling earth. “Speak, Cramer!” His nose was broken from hitting his face on the ground and he could feel that his gum had been cut.

“Help!” It was a small, pitiful cry, but even in the darkness Heath could locate its source. The boy was at his feet.

Heath felt about and found that a boulder, no less than two feet in diameter had trapped the boy’s legs to the ground, not to mention likely breaking one or both of them. Kneeling beside the boy, the major struggled to free him, pulling at the stone with all his might, trying to ignore the protesting of his injured shoulder. For a moment nothing happened. Then the stone shifted and finally slid off. Cramer was screaming in agony, but Heath ignored it as he lifted the boy out of the mud.

Cradling the private in his arms like a baby, Heath – for the last time – ran. His lungs felt as though somebody had filled them with methane and struck a match. His head was spinning with pain and he could scarcely focus on the light at the end of the tunnel.

Suddenly he was there. Lawrence and Durst had just dropped back into the tunnel to come rescue him and they caught Heath and the boy.

“Major, I’m so sorry! I thought you were right behind…”

But Heath wasn’t listening. He could feel himself collapse and then felt himself lifted through the hole from the tunnel into the trench above. He could feel wind and rain on his cheeks and fresh air in his lungs. He was safe, his men were safe, the trench was safe and he had done his duty.

In the middle of a filthy, rat-infested trench, Major David Heath felt safe. As shells squealed overhead and machinegun bullets rattled through the heavy air of no man’s land, he fell into an exhausted sleep.

A fine story.

ReplyDeleteI think somebody might have a writing career.

ReplyDeleteBest of luck.